Paying attention these days can be quite difficult.

As we examined in another article on why we’re so distracted so easily, beyond just the daily temptations of technology, our brains were simply designed to be distracted.

So with this being the case, what can we do to be more attentive to the things we do and the people around us?

The action of attention

First, it’s important to understand what exactly happens to our brain when we pay attention.

The general idea of attention is that it acts like a spotlight, focusing on one thing alone.

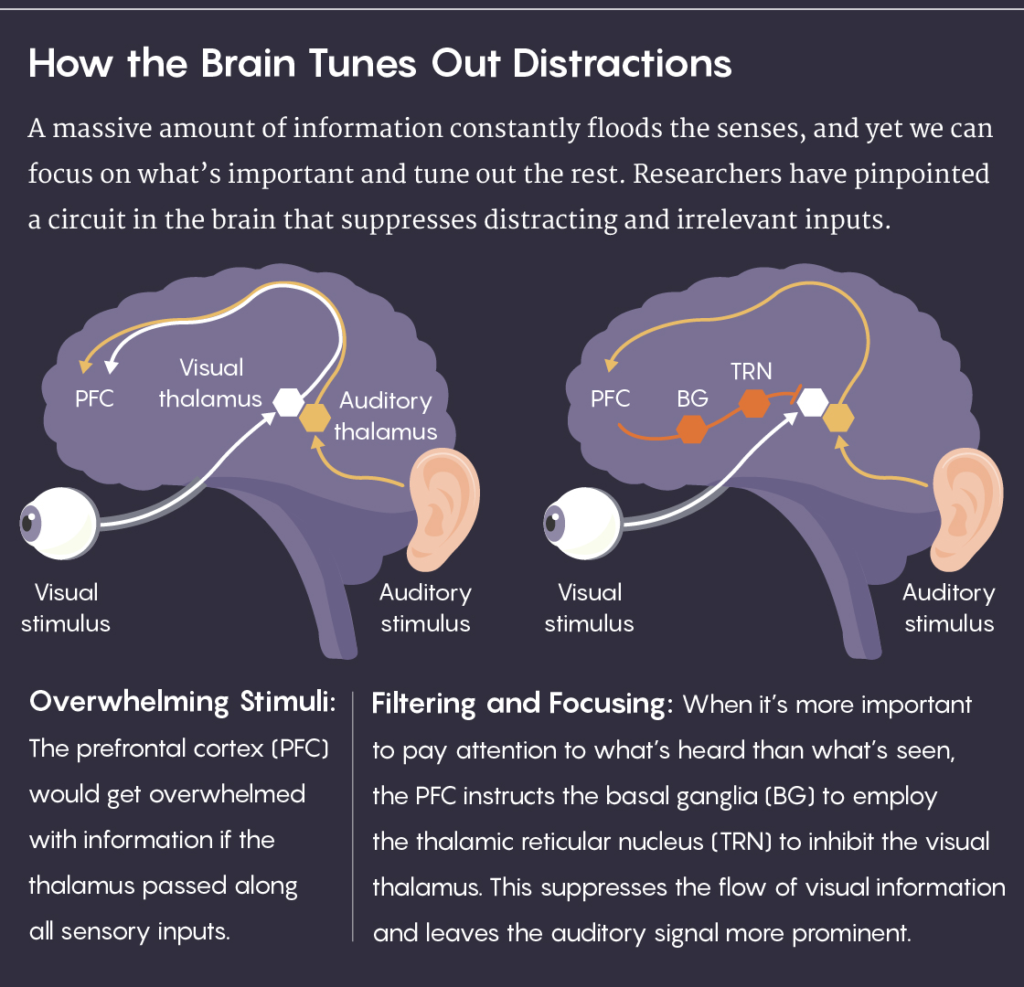

Recent research indicates that the way our brains behave is quite different from that. In fact, attention is more a matter of filtering, than spotlighting. We aren’t simply shining a light to a given thing when paying attention, but instead, we are suppressing lights everywhere else to filter in what we feel we need to give attention to.

Previously, it was noted that the prefrontal cortex — the part of our brain that gives commands to other regions — played a key part in attention. While this still remains to be true, further studies done by Michael Halassa, a neuroscientist at MIT, have shown that there are other deeper circuitries at play, ancient areas which previously, were believed to have no part to attention.

According to his research, the full circuit of attention, extends from the prefrontal cortex, all the way to the basal ganglia — the part of the brain associated with motor control. As John Maunsell, a neurobiologist at the University of Chicago states,

“The notion that motor structures are involved in this … is appropriate, in a way — that they should be right at the heart of the process of deciding what you will attend to next, what you will focus your sensory resources on next.”

— John Maunsell, Neurobiologist

This discovery changes the way we see, not only attention, but perception and cognition as a whole. The involvement of motor systems shows that what we perceive doesn’t only affect how we behave, but it goes both ways — how we choose to move and act shapes the input of what we perceive and attend to as well. As Heleen Slagter, a cognitive scientist at VU University Amsterdam notes,

“We experience the world not just using our bodies, but because of our bodies. And brains represent the world in order to meaningfully act in it. ”

Five different types of attention

We also like to think of attention as a straightforward, singular process but in fact, it’s actually a group of sub-processes. According to Sohlberg and Mateer’s Clinical Model of Attention, there are five types of attention.

- Focused attention — This is our ability to focus on a given stimulus, both internal and external. It can involve auditory, visual, tactile, and cognitive stimuli.

- Sustained attention — The ability to stay focused on something for a long period of time. When we achieve sustained attention, our brain is filtering through many pieces of information and prioritizing it accordingly. This process of sorting through and suppressing irrelevant, unimportant information is what is known as efficient selection.

- Selective attention — Just as the name implies, this is the ability for us to select and choose a given stimulus we want to be attending to. An example of this is when we are focusing on a given task, despite having various sounds or visual distractions happening around us.

- Divided attention — This is our ability to simultaneously respond to different stimuli, dividing our attention up into chunks. For example, when we are multi-tasking, we are engaging in alternating attention. While we may think this type of alternating between tasks is quite useful and efficient, studies have shown that the act of multi-tasking can be damaging to our brains.

- Alternating attention — This is our ability to alternate between different stimuli, moving from one thing to another. The difference between this and divided attention is that, we are allocating our attention to one given thing, instead of dividing it up into multiple parts.

Habits to help you focus

To concentrate better, we need to start by improving our attention. While aging is out of our control, according to Dr. Kirk Daffner, a Neurologist and Director of the Center for Brain/Mind Medicine at Brigham, there are three things we can be more aware of to improve attention.

- Cognitive training — These days, there are plenty of apps and websites that gamify cognitive training, which helps to improve response times as well as attention. The more you play, the more cognitive activity your brain is going through, which can help in daily life.

- Mindfulness — Meditation is great, but mindful meditation is even better. The act of being mindful is all about learning to focus your attention on the present moment, honing in on your breathing and thoughts. In a world where we’re constantly always on and plugged into something, mindfulness is an important step to sitting still — even just a few minutes every day — and paying attention to that which surrounds you.

- Exercise and sleep — Studies have shown that there is a direct correlation between exercise and increased cognitive ability. Regular, consistent exercise (even if it’s just a few minutes a day) is well-known to improve concentration, motivation, and mood. We get a boost of dopamine in our brains and as a result, this helps to increase our focus and attention. Like a domino effect, this can then improve the quality of sleep we have, which is also extremely vital for fostering attention.

“When you exercise, you increase the availability of brain chemicals that promote new brain connections, reduce stress, and improve sleep. And when we sleep, we reduce stress hormones that can be harmful to the brain, and we clear out proteins that injure it.”

— Dr. Kirk Daffner, Neurologist and Director of the Center for Brain/Mind Medicine