When was the last time you went on a trip somewhere? How was it?

You might be thinking of that time when you met and stayed up all night, speaking for hours at the local hostel with a stranger you had just met in Spain. Or perhaps you’re thinking about that time you backpacked in the mountains of Vietnam and lost your wallet, scrambling to find it. Or maybe all you can remember is that time you got food poisoning and had to end up staying in for most of that trip.

Whatever memory comes to mind, ask yourself: was that all there was to that trip? Or are there things you may be leaving out?

What is the Peak-end rule?

Memories are not perfect, as evident from other biases such as the misinformation effect and cryptomnesia.

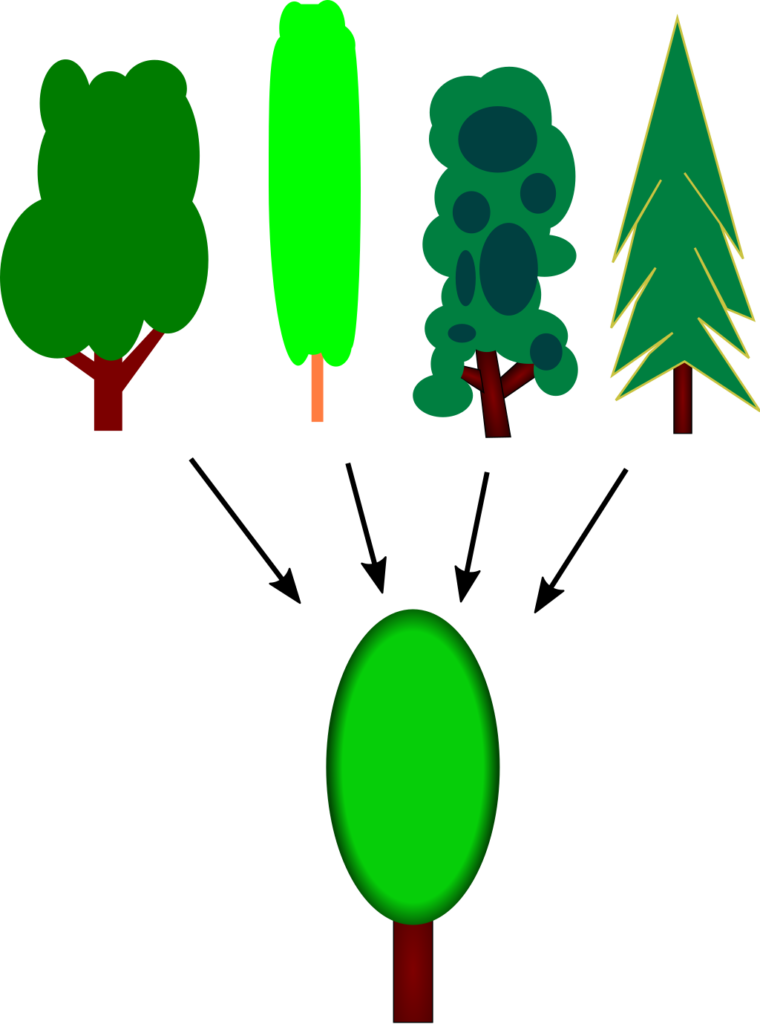

We often think of our memories as an episode reel of events, yet in truth, the way we remember acts more like a collection of momentary snapshots scattered across our minds. These experiences are sorted by the moments that stick out to us the most (whether pleasant or painful).

The Peak-end rule refers to this very mental process of putting great weight on the high intensive moments (also known as ‘the peaks’), as well as the final moments (the ‘end’) of a given experience. It is these distinctive moments that average out into a collage of memory that is then used to define our interpretation of the past.

So when we think about that last trip we went on, whether we deem it as a positive or negative experience is largely based on the aforementioned ‘peak’ and ‘end’ moments. Everything else in-between sort of fizzles out the cracks of our minds.

Where it comes from

The theory was introduced by the highly popular Israeli-American psychologist Daniel Kahneman, who clearly defined the bias as follows:

“The peak-end rule is a psychological heuristic in which people judge an experience largely based on how they felt at its peak (i.e. its most intense point) and at its end, rather than based on the total sum or average of every moment of the experience.”

— Daniel Kahneman

Kahneman et al. introduced this concept in 1993, in a study titled When More Pain is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End. In the study, the researchers had participants go through two different versions of an unpleasant experience. The first version of the experience involved participants submerging their hand in 14 °C water for 60 seconds. The second version got them to do the same, except once the time was over, they were subjected to keeping the hand submerged for another 30 seconds as they raised the temperature to 15 °C.

Afterward, the participants were asked which version of the experience they were willing to repeat and remember. Surprisingly, the majority of them chose to the second version of the experience. As noted by Kahneman et al. in their paper,

Subjects chose the long trial simply because they liked the memory of it better than the alternative (or disliked it less)

When More Pain is Preferred to Less (1993)

These results were interesting to note as they went against the very logical principles of temporal monotonicity, which refers to the idea that adding moments of pain to an end of an episode makes the experience worse while adding moments of pleasure makes it better. Despite having to expose their hands to uncomfortable temperatures for 30 seconds longer, the participants still chose to go with the second.

Why it happens

There are two other cognitive biases that cause the Peak-end rule.

The first one is the representative heuristic, which refers to a mental shortcut our brains make to make a decision about something. This helps to make quick judgments to help us in times of uncertainty. It is our brain’s way of computing a given scenario or thing, assessing the object, and organizing them into a general category we’re already familiar with.

Kahneman and fellow researcher and psychologist Dr. Barbara Fredrickson note that the value of the memory snapshots is what dominates the value of the experience. The emotional intensity we felt of a given experience is more influential to whether we remember it, rather than the duration of it itself.

Secondly, people also tend to remember things at the beginning or end of an event, due to the serial position effect. Made up of the primacy and recency effect, the ladder causes us to recall things that are more recent. As such, when it comes to our memories, the Peak-end rule places heavy emphasis on the end of an experience.

The American writers and academics, Chip and Dan Heath refer to the peak-end rule in their book ‘The Power of Moments: Why Certain Experiences Have Extraordinary Impact.‘

“When people assess an experience, they tend to forget or ignore its length. What’s indisputable is that when we assess our experiences, we don’t average our minute-by-minute sensations.

— Chip and Dan Heath, The Power of Moments

What to do about it

We need to remember that not all memories and experiences are defined by the high-intensive moments and end alone. Remembering events in this way alone is not accurate to the actual experience, and may in fact make some experiences feel more positive or negative than they actually were.

For this reason, it’s important to look back at our memories and try to see the experiences we had as what they were in their entirety. Reflecting on the events that occurred in a bigger picture may help to change our perspective on the memory itself – allowing us to see that things weren’t all that bad as we may have thought, or perhaps not as purely pleasant as imagined.