We are living in a time of great uncertainty.

From an incoming economic recession, high inflation rates, lingering pandemic, and continuous ongoing war, we are surrounded by uncertainty all day, every day.

Since ancient times, we’ve always been faced with unpredictable circumstances, and yet over the decades, our brain has learned to adapt and recognize patterns on autopilot.

This has become so automatic that now, when faced with uncertainty, our brains are put in states of anxiety, negatively affecting the way we live.

How our brains decode ambiguity

Our brains are not meant to deal with ambiguity. In states of high uncertainty, parts of our brain circuitry get skewed which negatively affects how we make decisions.

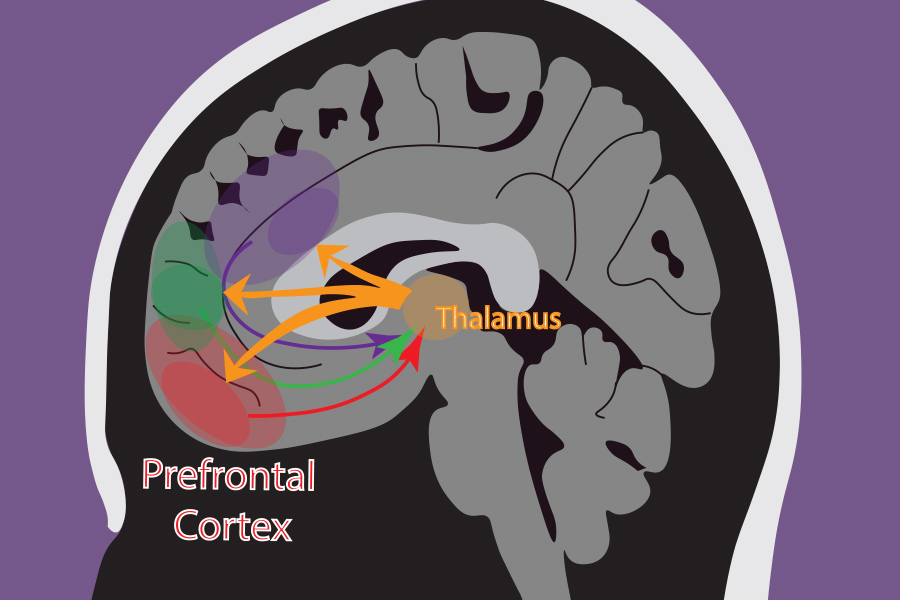

A brain imaging study shows us that when people look at a specific scene and are unsure of what to pay attention to, the part of the brain known as the mediodorsal thalamus is activated. This is a huge component of understanding uncertainty, as the researchers found that the less guidance the participants had for a given task — in other words, more uncertainty — the more active the mediodorsal thalamus became.

This region of the brain is important to note as it serves as sort of a crossroads that is made up of cells connecting different regions with one another. The mediodorsal region sends signals to the prefrontal cortex. This is the area where sensory information integrates with the things that guide our behavior — our goals, desires, and knowledge.

In a study conducted by Michael Halassa, MIT Associate Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, they looked at a group of mice and gave them a set of tasks to execute. In their research, they discovered that when completing a given task, the prefrontal cortex activated every time. Yet, it was only when the mice had no idea what to do or how to behave, that the mediodorsal thalamus came into the picture.

“One area cares about the content of the message — that’s the prefrontal cortex — and the thalamus seems to care about how certain the input is.”

— Michael Halassa, MIT Associate Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences

Our brain in uncertainty

As mentioned earlier, during the hunter-gatherer period of human civilization, we were faced with unpredictable situations every day. The brain was used to uncertainty. Yet, as civilization developed and got comfortable, our brains have evolved to become uncertainty-averse.

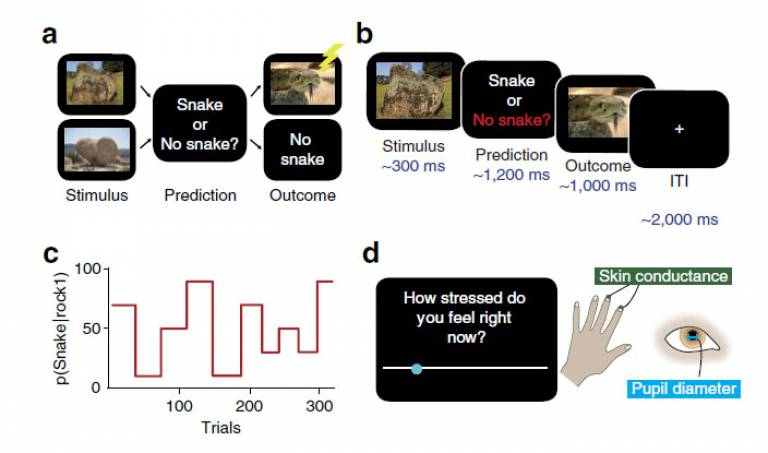

Now, even the taste of uncertainty affects our brain badly, as scientists have found that psychological uncertainty can be just as painful as actual physical pain itself. For example, in one study, participants were involved in a simulated game of rewards and punishments. Subjects were told that they would get a 50/50 chance of receiving an electric shock. Researchers found that the participants who anticipated the possibility of such a shock and experienced more stress than those who knew with full certainty they’d receive the shock.

According to one research, they found that dealing with uncertainty takes up a lot of ‘cerebral energy.’ In times of uncertainty or ambiguity, our selfish brain demands extra energy from the body. This becomes troublesome if the feeling of uncertainty is not alleviated, as our brains continue to pull for more brain energy, which in turn will create a sort of ‘energy crisis’ that burdens the individual. If this goes on for long enough, this consistent load and unmet demand can lead to brain malfunction in the form of impaired memory, reduced performance, and subsequent cardio- and cerebrovascular events.

For this reason, prolonged uncertainty can be quite detrimental to our brain. It can lead to decreased motivation, concentration, self-control, and a decline in our general well-being. This impairment in working memory can also prevent you from being able to solve problems effectively and sustain any ideas mentally, thus slowing long-term memory recall significantly.

Changing the way we think

Uncertainty doesn’t have to be something we are controlled by.

Knowing how uncertainty affects our brain and using that knowledge to change the way we think is one of the best ways to overcome the weight of uncertainty.

Learning to be more realistically optimistic is one way that psychologists have deemed as facing uncertainty better. Social psychologist Albert Bandura referred to this idea of building a strong sense of self-efficacy, where we stay positively motivated in the face of adversity. Believe it or not, believing in yourself matters.

As academic and professor of Psychology Gabriele Oettingen notes in her research, mental contrasting urges behavior to be aligned with a goal when expectations are high, while goal-directed behavior is far less when expectations are low. In other words, by practicing in realistic optimism, you prepare yourself for when things don’t go as expected, while optimism just for the sake of optimism (unrealistic), will set you up for failure.

Psychologists also borrow from the construal level theory, which refers to the idea that the more distant an object or event is from a person, the more abstract the thoughts will be, while the closer it is, the more concretely we’ll think about it.

Research shows that the level of construal used to think about our actions has a significant impact on our behavior. What this means in the context of anxiety is that, oftentimes, the things that we feel we cannot control and are far off in the distance, we may find ourselves at a lower level of construal, thus seeing the object or event as abstract, thereby feeling demotivated and lost. Instead, what we need to do is reframe the way we think about things, and reach for higher levels of construal, focusing on what matters most in terms of purpose. It’s this type of mindset that will help our brains remain resilient in times of uncertainty.